B a c k / N e c k

Surgical and non-surgical interventions for spinal disorders

B a c k / N e c k

Orthopaedic and Spinal Surgeon

MBBS (Hons 1) MS (Ortho) Dip. Anat FRACS FAOrthA PFET (Spine) GEPI CIME

Adjunct Assistant Professor, Bond University, Queensland

P - 0499 NEC BAC

[0499 632 222]

F - (07) 3009 9992

P.O. Box 211 Isle of Capri QLD 4217

Spinal anatomy and disorders

Please note that the following section contains medical images and graphics

-

Spinal anatomy basics

-

Herniated discs and common surgeries – Low back

-

Herniated discs and common surgeries – neck

-

Spinal stenosis

-

Spinal fusion and reconstruction

-

Facet joint degeneration

-

Scoliosis and kyphosis

-

Spondylolisthesis (slipped vertebrae) and Spondylolysis (Stress fractures)

-

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

-

Coccydynia (Coccyx pain)

-

Osteoporotic spinal fractures

1. Spinal anatomy basics

There are ‘special’ areas of the spine and special vertebrae which are different from the ‘standard’ vertebrae including the very top between the skull and upper neck (atlanto-occipital C0-1 and atlantoaxial joints C1-2) and very bottom of the spine between the sacrum and ‘tailbone’ (sacrococcygeal area). The cervical and thoracic vertebrae and discs tend to be smaller while the lumbar spinal vertebrae and discs are larger and the same can be said for the canal and foraminae (tunnels where the nerve sac branches travel through).

There are five bones (known as vertebrae) that comprise the lumbar (low back) spine, 12 vertebrae in the thoracic (middle/rib cage) spine and seven vertebra in the cervical (neck) spine. Approximately 10% of the population can have extra vertebrae or atypical anatomy, for example having extra sacral or lumbar discs. Between each of these vertebra (intervertebral space), lies the intervertebral disc, which acts as a shock absorber during back movement. The intervertebral disc is susceptible to the aging process, and it can lose its elasticity and water content over the years with progressive weakening of the tough outer tyre (annulus) that contains the gel-like water rich inside contents of the intervertebral disc (nucleus pulposus).

Most standard vertebrae have the disc and vertebral body facing the front of the body, towards the face, chest or the abdomen, tunnels for the nerve roots to exit out of left and right at each level and a central portion (canal) for the nerve sac to run through. The facet joints are paired left and right joints at the back of the vertebrae that connect between each level. There are bony prominences called the transverse processes projecting out horizontally perpendicular to the disc and vertebral body and a spinous process which projects out to the back of the body. Special ligaments connect these prominences and provide attachment for muscles to act on your spinal column. These all act harmoniously in a healthy spine as a big unit referred to the musculoligamentous envelope. Muscle health is extremely important in the functional movement and protection of the spine – wasting and fat replacement in postural endurance stabilizing muscles is extremely common in patients presenting with back and neck pain.

The spinal cord comes down from the brain into the spinal canal and in the average adult ends around L1/2 level. Here a relay station is situated called the Conus Medullaris. From there, the sac becomes a bundle of peripheral nerves called the horses’ tail (Cauda Equina – Latin). Injury to the spinal cord and conus medullaris can cause devastating weakness and numbness in the legs and/or trunk and hands depending on the location. Compression and injuries to the cauda equina tend to be more subtle, progressive and do not generally show as a dramatic presentation unless there is substantial sudden compression or narrowing (‘stenosis’) such as that caused by a large disc prolapse, bleed, infection or tumor. At each spinal level there tends to be a central nerve sac like a tree trunk and paired left and right branches off the spinal cord. Compression to the branches tends to produce more specific and localized signs (often one sided) and symptoms like pain and weakness related to the areas the nerve affected supplies neural electricity to.

Herniated lumbar (low back) discs are extremely common and twin studies show they usually are degenerative (due to genetics & ageing) but may also result less commonly from explosive trauma, repetitive loading and unusual forces. Herniations that occur from lifting or twisting loads tend to have associated underlying degeneration. Usually the disc has a jelly-like water & protein filled inside (nucleus polposus) which is very irritating when exposed to nerve structures and a tough outer ‘tyre’ like layer (annulus fibrosus) which keeps the nucleus polposus from leaking out. Nutrition occurs in the disc when it is intact and allows nutritents to flow through one end of the vertebrae (endplate) through the disc to the other endplate on the other side. Once the inner disc is internally disrupted in adults it does not tend to heal as it has no blood supply. However, disc fragments that ‘pop out’ or expose themselves outside through tears in ‘the tyre’ can be recognized by the immune system and either shrunk or removed with time. Due to this ~60% of patients are resolved by 6 weeks, 80-85% of people with new onset pain from a rupture disc have resolved or nearly resolved their symptoms by 3 months and 90-95% by 6 months. If the pain progresses beyond this point the chance of spontaneous resolution is less and studies show that most of these patients go on to have chronic persistent pain. A portion of these patients with chronic pain likely have highly sensitized nerve tissues grow into the tears in their annulus that causes ‘discogenic pain’ as discussed below.

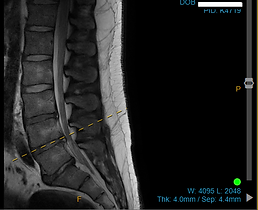

Patient with a large L5/S1 prolapse – note there is a large annular tear acting like large hole in a tyre allowing the disc material to escape backwards into the spinal canal and compress the nerve sac.

While a large proportion of herniated discs do not cause symptoms they can be a cause of back pain, leg pain or both. They can irritate nerve structures from either mechanical pressure, leakage of inner disc chemicals or both. This irritation can present itself by travelling down to the legs and/or buttocks (colloquially known as sciatica) usually in the distribution of sensation that the irritated nerve is usually responsible for. Also, the disc tear itself can become painful when nerves abnormally grow into the tear and become sensitized (discogenic back pain) and any prolonged or excess pressure can produce back pain. Some classic features of discogenic back pain include pain with below waist bending, prolonged sitting or standing, pain with forward bent postures (e.g. shaving or washing face at basin), unplanned jolts or twists and relief with lying down. These features are often present when a degenerate or bulging disc has tears that become filled with sensitive nerve tissue (see picture below). While a history and a patients young age can be suggestive of the disc as the source of back pain it is sometimes confirmed by discography, injection of contrast into the disc, or by MRI with spectroscopy - a virtual chemical analysis of the disc which can suggest which disc(s) is likely to cause pain. When a disc is extruded beyond the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) or sequestered and 'spat out' of the disc (see below), the immune system often can recognise that the disc material is in a place it does not belong, and after a period of inflammmation that can cause nerve pain and symptoms, the disc prolapse can be absorbed by the body and symptoms can dissipate. Sometimes, despite a disc prolapse shrinking and the pressure disappearing off a nerve, permanent changes to the nerve can occur.

(Left) Stages and descriptions of disc degeneration. (Right) MRI with spectroscopy - a novel method of virtual analysis of discs which can suggest discs that are likely to be pain generators.

“Sciatica”, or lumbar radiculopathy, occurs when spinal nerve compression causes shooting or burning pain down the the leg and/or buttocks, commonly beyond the knees and occasionally into the foot. It can be from any cause of narrowing of space for the nerves but in the younger patient is usually due to disc prolapses whereas in the older patient is usually due to joint overgrowth, bone spurs or ligament enlargement. Sciatica, or neurogenic claudication due to stenosis, may also be associated with numbness or pins and needles in a particular region of the leg supplied by the compressed nerve (dermatome). Occasionally sections of the leg muscles may become weak due to nerve compression.

Most lumbar spinal disc issues do not require surgery. This is as most herniated discs respond well to conservative treatments and time and injections are sometimes beneficial to manage pain as mostly the body will heal the herniation and associated pain. Conservative treatment typically includes short rest, avoiding aggravating activities, medications, heat, improving self care (sleep hygiene, weight and stress management, good nutrition), stretches as well as various passive and active treatments (physiotherapy, chiropractic, osteopathy, massage, acupuncture, yoga, tai qi, pilates, TENS machines, capaiscin creams)

Urgent or semi-urgent surgery is considered for major nerve dysfunction and power loss associated with pressure on nerves. Sensory change or pain alone (i.e. no there is significant neurological compromise such as weakness) usually is treated with a conservative approach unless pain is unbearable and conservative treatment has been tried for a reasonable time (at least 4-6 weeks).

For such disc prolapses that mainly present with buttock or leg pain and signs of nerve compromise then patients and focal or sequestered discs tend to do well with removal of the compression on the nerve by discectomy (removing the prolapsed part of the disc) or decompression with laminectomy (removing a wider area of bone and any enlargement of the surrounding joints or bone spurs touching the nerve in addition to the disc prolapse). To reiterate, discectomy involves surgical removal of protruding intervertebral disc material through opening a small channel in the bony ring around the nerve sac. This surgery may be performed using a microscope, also known as microdiscectomy. The aim of the surgery is to remove disc material that is protruding or loose and is compressing the nerve root, the remainder of the intervertebral disc is generally not removed.

The corridor and amount of bone removal (orange lines) needed to achieve a discectomy and remove the protruding disc (orange star) is relatively minor compared to a laminectomy. Schematic depicting discectomy on right.

Example of an extruded disc fragment (placed in formalin) removed from a discectomy.

Laminectomy involves removal of a wider area of the bony ring, between the facet joints, converting the bony ‘O’ ring to a ‘U’ which allows the nerve sac to sit without being ‘pinched’. See the diagram below and an example of the bone removed.

Example of far lateral and foraminal disc prolapses and use of an oblique (Wiltse) approach and tubular minimally invasive (keyhole) surgery approach to remove lateral discs/bone spurs located off centre that compress the exiting nerve roots

‘U’ shaped piece of bone being removed off a tight nerve area – note the nerve underneath

An example of a piece of bone removed from a laminectomy to convert the ‘O’ around the tight nerve region to a ‘U’ where the nerve can be afforded more room. See the nerve sac now free.

A foraminotomy (often performed as a keyhole type procedure) involves expansion and opening up of a narrowed tunnel that the nerve is crowded or compressed within, thereby creating for space for it to exit without any pressure. An example above of nerve roots affected by exit tunnel narrowing e.g. by bone spurs or disc in the picture on the left. Bottom left - narrowed space for nerve preoperatively and demonstration of improved space for the exiting nerve postoperatively (yellow) with the surgical tract used (green). On the right an example of a completed foraminotomy (bottom) and the bone removal required to achieve decompression (middle).

The prognosis is not as favorable if the patient has had previous spine symptoms, if there is a large annular tear (>5mm) or if the whole spinal segment has advanced degeneration with disc collapse, bone spurs, diffuse wide bulging and narrowing of the tunnels that transmit the nerves. If pain becomes chronic (>6 months) then it is much less likely to resolve spontaneously – at this point consideration may be given to surgery whether decompression (taking pressure off nerves to legs by removing disc material or protruding bone that contacts it) or reconstruction (removing the ‘sick’ disc and in its place inserting an implant such as a fusion device or disc replacement). The rationale for the latter is that the unhealthy disc is not likely to heal itself and is more likely to have recurrent prolapses and symptoms. Results of surgery to remove disc prolapses or fragments where the main symptom is back pain is less predictable.

(A) A normal disc and the relevant nerve innervation in the back of the disc (posterior annulus) and nearby (the dorsal root ganglion relay station)

(B) Abnormal painful situation where a tear in the disc allows chemicals to exit the inner disc causing irritation to the nerves nearby (orange) as well as allowing small pain nerves to grow into the abnormal tear and become sensitised causing back pain (red colour). (C) Small tears in the disc allow ingrowth of nerves and inflammatory tissue into the annular tears (red colour) but without leakage of the inner chmicals, not producing any referred nerve related pains. Right image- complex network of pain and sensory nerves around the disc and vertebra

Post discectomy and laminectomy patients should not sit for prolonged periods (over 1 hour) for approximately two weeks and should, therefore, not drive for that period. They should also not perform any tasks which may involve repetitive forward bending and/or heavy lifting (over 10kg) for approximately six weeks. All patients are encouraged to commence a gentle mobilisation and muscle strengthening program within two weeks of the surgery and are reviewed routinely by a Physiotherapist prior to their discharge from hospital.

Spinal fusion involves the purposeful stiffening and joining of two or more spinal segments to prevent motion where the segments are considered dysfunctional or painful. The aim can also be to realign the spine and increased height available for the nerve branches to exit out of the spine unimpeded, counteracting a ‘flat tyre’ effect. Spinal fusion may be performed for lumbar stenosis when there is evidence of severe foraminal stenosis, spinal deformity or instability such as degenerative spondylolisthesis or retrolisthesis.

Left - Large herniated L4/5 disc prolapse compressing the cauda equina nerve sac. Note the disc where the prolapse has come from itself is significantly degenerative and the vertebrae are almost touching. Middle and right pictures - Top represents a male with a L5S1 disc extruded fragment and L45 bulge - resolution after 12 months on the bottom row of size of L45 bulge and disappearance of L5S1 fragment.

2. Herniated Discs

Herniated discs in the cervical (neck) spine can present with arm and/or shoulder symptoms but generally have a favorable outlook. They are extremely common and usually are degenerative (due to genetics & ageing) but may also result from trauma and unusual forces. Usually the disc has a jelly-like water filled inside (nucleus polposus) which is very irritating when exposed to nerve structures and a tough outer ‘tyre’ like layer (annulus fibrosus) which keeps the nucleus polposus from leaking out. Once the inner disc is internally disrupted in adults it does not tend to heal as it has no blood supply. However, disc fragments that ‘pop out’ or expose themselves outside the tyre can be recognized by the immune system and either shrunk or removed with time. As distinct from disc prolapse or bone spurs irritating the nerves as they exit off the spinal cord (like branches off a tree trunk) pressure or dysfunction of the spinal cord itself (myelopathy) is a more serious condition.

Spinal conditions in the cervical spine commonly present not just with neck pain but with pain down the arms, shoulder blades and back of head (occipital) headaches. Numbness, loss of function and dysfunction (such as abnormal reflexes and disco-ordination) in the legs, abdomen, bladder or bowels can be more worrying symptoms.

The majority (approximately 80-85%) of neck disc prolapses with irritates nerve branches improve without surgery if there the dominant symptom is pain (even with minor pins and needles or minor weakness) by the 18-24 month mark with the best prognosis indicated by rapid improvement before 4-6 months. If there are signs of spinal cord distress or major power loss then the prognosis is not as favorable without surgical intervention.

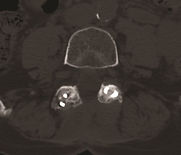

Example of a left sided disc prolapse at C5/6 shown in cross section – while it is touching the spinal cord itself, the main effect is to crush the exiting left C6 nerve

Conservative treatment typically includes short rest, avoiding aggravating activities, nerve root injections, medications, heat, improving self care (sleep hygiene, weight and stress management, good nutrition), stretches, various passive and active treatments (physiotherapy, chiropractic, osteopathy, massage, acupuncture, yoga, tai qi, pilates, TENS machines, capaiscin creams)

As opposed to simple disc prolapses, cervical stenosis and cervical myelopathy are more sinister conditions as they typically do not have as good a natural history as disc prolapses. Cervical stenosis, often from a combination of disc or bone spur contact on exiting nerves can typically cause pain in a nerve root distribution as well as sensation and power changes. Cervical myelopathy, often associated with aging where there is a combination of disc and bone spur encroachment onto the spinal cord, can be a dangerous condition that when diagnosed typically requires surgery.

Example of disc bulges causing cervical stenosis (tightness) and myelopathy (arrow showing swelling in the spinal cord).

If surgery is required for a disc prolapse or bone spur causing symptoms from irritated nerves then the evidence suggests that best results are achieved when the duration of symptoms are less than 6 months. In other words, conservative treatment including injections should be tried initially but failure to respond by 4-6 months indicates surgery. Surgery is very effective in removing pain and dysfunction around the arms and shoulder but is less predictable in eliminating headaches and neck pain. When surgery is required, most cervical conditions can be addressed through an anterior approach (from the front of the neck) which avoids damage to the stabilizing muscles and joints and has a lower risk of paralysis, wound breakdown and infection. Posterior approaches may be advised where tunnel exit narrowing alone is the major problem, where there is tightness of the spinal cord on multiple levels or at the top or bottom of the cervical spine (c0/1, C1/2 or C7/T1)

Herniated discs commonly present with signs and symptoms of irritation of usually one, but sometimes multiple spinal nerves. See diagram below for back (lumbar) disc herniation examples of irritating L4, L5 and S1 nerves in each example on the left and irritating the cervical nerve roots C4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and T1 on the right.

Some examples below of different types of injections to treat spinal pain including an epidural steroid - ESI, nerve root block - NRB (both for nerve pain) and facet block (for facet joint pain)

4. Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis refers to narrowing of the tunnel(s) that transmits the nerves. Central refers to the spinal cord in the cervical and thoracic areas and spinal (thecal) sac in the lumbar spine. Foraminal stenosis refers narrowing affecting the branches coming off like branches off a tree trunk to the sides. Stenosis can be due to longterm degeneration from bone spurs, calcium buildup and general loss of height or alignment or can be more rapidly acquired due to disc bulges, bleeding, tumors and infection.

In the cervical (neck) spine and thoracic spine (Rib cage area) any narrowing or compression affects the spinal cord itself and this can produce extremity (arm and leg) symptoms but also abnormalities of the bowel, bladder, abdomen, general balance and reflexes. In the lumbar spine (lower back) compression tends to affect the ‘cauda equina’ (horse’s tail in latin) or, if higher up in the lumbar spine, the conus medullaris – a relay station between the spinal cord and the spinal peripheral nerve sac. The most common expression in the community and medical circles indicating probable stenosis is “sciatica”.

“Sciatica”, or lumbar radiculopathy, occurs when spinal nerve compression causes shooting or burning pain down the the leg and/or buttocks, commonly beyond the knees and occasionally into the foot. It can be from any cause of narrowing of space for the nerves but in the younger patient is usually due to disc prolapses whereas in the older patient is usually due to joint overgrowth, bone spurs or ligament enlargement causing “stenosis” (narrowing of the nerve tunnels). Sciatica may also be associated with numbness or pins and needles in a particular region of the leg supplied by the compressed nerve (dermatome). Occasionally sections of the leg muscles may become weak due to nerve compression. It is usually associated with being upright and walking but even can occur at rest or when lying flat (restless legs and cramps).

Proposed Queensland Criteria for Discogenic Low Back Pain [Based upon previous scientific literature and Currently being investigated and validated]

Lumbar canal spinal stenosis caused by bone spur intruding into the spinal canal.

Before and after anterior fusion and stabilisation of an L4/5 spondylolisthesis

Degenerative spondylolisthesis or retrolisthesis is when one part of the spine slips out of its normal alignment and over the other vertebrae. This condition is often associated with foraminal stenosis (narrowing of the tunnels where the nerves exit from). Stable slips often require no stabilising metalwork or considering of facet fusion only whereas grossly unstable levels typically benefit from interbody and or pedicle screw fusion.

Patient with a degenerative spondylolisthesis – note the slipped vertebra which was overly mobile. Xray of the same patient following a fusion to stabilise the segment.

In the neck, spinal stenosis of the neural foramen (tunnels out to the side of the spine) will commonly lead to combinations of headache, pain around the shoulder blades and arm symptoms. If there is stenosis in the middle of the spinal canal affecting the spinal cord then symptoms and signs can be more worrying (see discussion regarding ‘myelopathy’).

Stenosis in the thoracic region can also lead to myelopathy if central affecting the spinal cord, whereas is foraminal (the tunnels away from the spine) can present as symptoms radiating around the rib cage or even to the abdomen.

In rare cases, 'Sciatica' like symptoms can be mimicked by non-spinal nerve disorders - this includes nerve plexus irritation outside of the spine, referred pain from joints like the sacroiliac joint or hip [e.g obturator], peripheral nerve root entrapment [e.g. meralgia paresthesica], painful peripheral neuropathy and piriformis syndrome. The latter is a popular alternate diagnosis often proposed but is in fact quite uncommon and likely accounts for <5% of patients with neuropathic lower limb symptoms. Below is an example of genuine piriformis syndrome that received interventional treatment to divide and stretch the fibres compressing the sciatic nerve [images courtesy of Mermaid Beach Radiology]

5. Spinal Fusion and reconstruction

Spinal fusion involves the joining of two or more spinal segments to prevent motion and is usually achieved with a combination of removal of the disc and cartilage, placement of bone grafting material and stabilisation with either rods, plates, screws or a combination. On the other hand, spinal motion preservation aims to stabilise the spinal segment without restricting motion. Both techniques are broadly referred to as ‘reconstruction’ whereas techniques which take pressure of nerves only without attempts to realign, stabilise or restore lost height (e.g. discectomy or laminectomy) is referred to as ‘decompression.’ Often a combination of reconstruction and decompression is necessary.

Spinal fusion is a broadly applied technique for spinal conditions and may be used for spinal instability (e.g. ligamentous laxity, tumor, fractures), correction of deformity, increasing height of the disc space (to create more space for exiting nerves) or stabilisation of painful arthritic spinal segments. There is controversy about the role of spinal fusion in back pain surgery – it should only be employed where the cause of the back pain is clear (i.e. confirmed significant disc disruption where there is evidence of the painful level[s]) and there is a confirmed indication for surgery in a suitable patient. There is mixed evidence about spinal fusion but where performed for specific indications (e.g. spondylolisthesis, sacroiliac joint dysfunction) with correct patient selection there is high level supportive evidence.

Multiple described techniques exist to achieve spinal fusion including:

Lumbar spine

-

Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (ALIF) – through the front of the abdomen

-

Oblique Lumbar Interbody Fusion (OLIF) – obliquely through the abdomen

-

Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion (LLIF/XLIF) – side on through the abdomen

-

Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion (TLIF) – obliquely through the back

-

Posterolateral fusion (PLF) – grafting across the bone & joints at the back of the vertebra

-

Combined of above and posterolateral fusion (360 degree fusion)

-

Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (PLIF) – insertion of fusion cage around back joints next to the spinal nerves

-

Combined with disc replacement (hybrid)

Modern non invasive imaging techniques such as spectroscopy, or in this case, gadolinium enhanced MRI (pictures to the right with arrows) can assist in demonstrating the pathological discs which may (in combination with other findings) suggest that a disc is painful. The same patient scan without the enhancement shows how the pathology can be missed or underestimated. Traditionally invasive techniques such as discography (image far right) have been relied upon to show a disc is responsible for pain

Images courtesy of Dr Zane Sherif/Ben Kennedy - Mermaid Beach Radiology

Examples of anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) - top left, posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF)

- top right, lateral or extreme lateral interbody fusion (LLIF or XLIF) - middle left. Further are examples of a 360 degree fusion (combining either an ALIF or LLIF with posterior fixation with screws) - middle right and a lumbar hybrid procedure shown here with an ALIF at the bottom level and two disc replacements above - bottom left. Bottom right is a schematic showing the different approaches (in horizontal cross section of a lumbar spine)to the spine to place cage implants into the intervertebral space. Diagram describing indirect vs direct decompression

Cervical Spine

-

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion

-

Anterior corpectomy and fusion

-

Posterior fusion

-

Posterior Laminoplasty

Example of a 2 level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion - left image - and combined anterior and posterior fixation - right image.

Many of these types of fusions can be performed with minimally invasive techniques and also either robotically or with navigation - in some cases the planning as shown below can be done before the surgery. The latter techniques have been shown to be more accurate and have less hardware misplacement than conventional freehand or X-ray based (fluoroscopic) screw placement techniques. Some studies have even shown reduced infection, muscle damage and less construct failures.

Where possible, Dr. Zotti prefers to use the approach with the least amount of collateral damage and lowest possibility of short and long-term complications that enable the ‘right job to get done’. In the lumbar spine, this is typically anterior approach (especially for L5/S1) or lateral based techniques but posterior based correction is the workhouse for many conditions. In the cervical spine, the anterior approach is the standard of care for most common conditions in patients. Some of these approaches will benefit from involvement of other specialists such as vascular surgeons in the lumbar spine, cardiothoracic surgeons in the thoracic spine or ear/nose/throat surgeons in the neck.

Motion preservation techniques : as opposed to fusion, motion preservation such as lumbar and cervical disc replacement and cervical laminoplasty aim to correct the underlying segment issues without losing motion and transferring stresses elsewhere in the spine. There is now very good mid and longterm data to support the concept of motion preservation with good functional results and some evidence of reduced need for longterm fusions at adjacent levels and reoperations. Sometimes they can be combined with fusion at other levels to constitute a ‘hybrid’ surgery e.g. disc replacement at one level and fusion(s) at other levels as required.

An example of a cervical hybrid procedure – note that the fusion segment (plate and screws) does not move

while the disc replacement segment continues to move with different head and neck postures.

Example of cervical hybrid procedure.

Example of 2 level cervical disc replacement

Example of a cervical laminoplasty - the bony arch is refashioned by deliberate expansion of the space available for the spinal cord

6. Facet Joint and Disco-vertebral Degeneration - radio frequency pain procedures

Facet joint syndrome is an arthritis-like condition of the spine that can be a significant source of back and neck pain and is more common in the middle aged and elderly. It is caused by degenerative changes and abnormal mechanical loads to the joints between the spine bones at the back of the spine relating to aging. The cartilage inside the facet joint can break down and become inflamed or the joint can become irritated or stretched, triggering pain signals in nearby nerve endings. Facet pain is typically worse with inactivity, prolonged erect posture and is usually worse from waking up in the morning, worse with pressure on the joint (e.g. from manipulation) and associated with clicking and pain with extension and rotation. It is usually central localised dull pain but commonly refers to the top of the shoulder in the neck or in a band like distribution above the buttocks in the back. Select conditions respond well in the short to medium term to outpatient style spinal interventions - discogenic pain to disc denervation (biacuplasty) while discovertebral pain and bone on bone mechanical pain has been shown to respond well to basivertebral ablation.

(L) Diagram showing the layers of the facet joint an area where one can develop joint synovitis (inflammation of the joint lining)

(R) Facet joint arthritis and severe degeneration

Medication, physical therapy, joint injections, nerve blocks, and nerve ablations may be useful to manage symptoms. In select cases, chronic symptoms may require surgery to fuse the joint.

(left) radiofrequency ablation of the medial branches that carry pain signals from the facet joints (middle) disc biacuplasty - needles inserted to denervation the nerve within the back of the disc (right) the nerve is pulsed at the dorsal root ganglion relay station to desensitise pain signals (far right) basivertebral nerve ablation of the nerve within the vertebra

Examples of direct facet fusion using facet cage/graft/compressive screw construct

7. Scoliosis and Kyphosis deformity

Scoliosis is a 3 dimensional sideways (≥10 degrees) and rotational curvature of the spine. Occasionally an underlying nerve, muscle condition or bony abnormality may be the cause of the scoliosis. However, in most cases, no cause can be found (idiopathic) in the young. There may be a genetic predisposition for idiopathic scoliosis. In the older patient, it is more commonly due to degeneration (De Novo Scoliosis / Degenerative Scoliosis) or untreated scoliosis from youth. Kyphosis is an exaggerated stooped forward posture outside of the expected norms that can be developmental (Schuermann’s) or caused by trauma, fractures (multiple osteoporotic), trauma and aging (loss of disc condition). Some spinal deformity (malalignment) is caused by previous surgical interventions, particularly when the spine is fused in unnatural positions or there is excess strain on the mobile unfused portion of the spine - a common example of this is proximal junctional kyphosis, or PJK, where the spinal 'falls off' the top of a screw/rod construct. A major contributor to PJK is the patient not being fused in a harmonious spinal curvature and, instead, being fused 'too straight' - this is called 'flat back syndrome'.

Example of a kyphotic (exaggerated forward) thoracic posture

Example of a lumbar scoliosis (curved and rotated) posture

Example of a PJK failure above a spine fused in a 'too straight' position (flatback deformity)

Treatment for scoliosis and kyphosis is dependent on the severity of the curve and age of the patient. Most patients just need close observation of their scoliosis or kyphosis with the most accurate assessment being via automated methods (EOS™ scan). Specialised physiotherapy or bracing may be appropriate in the growing patient. If non-operative treatment fails, then surgery to either correct the deformity or cease its progression may be considered.

8. Spondylolisthesis (slipped vertebrae) and Spondylolysis (Stress fractures)

Pars fracture, also known as spondylolysis or pars defect, is a stress fracture or break involving the small inter-connecting part of the lumbar spine. This condition is commonly seen in gymnast, dancers, athletes, cricket players and football players where a lot of stress is being placed on the pars. Some patients may not be aware they have spondylolysis (pars fracture) until they have x-ray taken of their back. Symptomatically, patients experience pain of the lower back, extending down through the buttocks and hamstrings.

Spondylolisthesis is also commonly known as slipped vertebra. Spondylolisthesis in the younger population occurs when the pars defect results in failure to maintain spinal alignment and the vertebra slips forwards out of normal position and over other parts of the spine. Back pain can result from instability and from cumulative disc degradation from abnormal forces. When the slipped vertebra is severe, nerve roots can be stretched or ‘pinched’ causing shooting pain down the back of the legs and into the foot. Numbness in the foot and weakness of the muscle supplied by the nerve may occur.

Example of pars defect (green arrow) which has gone on to result in a slip (spondylolisthesis) of L5 on S1.

Most patients with spondylolysis and/or spondylolisthesis may improve without surgery. A period of rest and avoiding participation in any sporting activities may be advised following acute pars fracture, allowing time for the fracture to heal. Similarly, patients with spondylolisthesis may get better following a treatment plan of physiotherapy (core and multifidus strengthening), bracing for selected cases and lifestyle changes including losing weight. If non-operative treatment fails, then surgery may be required. Pictures on the right demonstrating a non-fusion technique (repair) to stabilise the pars area and allow it to heal

Surgical treatment for patients with spondylolysis may include repair of pars or spinal fusion.

Pars repair is performed when there is no slippage of the vertebrae and the associated disc is reasonable quality. The procedure involves inserting a screw across the fracture to stabilise and encourage healing.

Typically, surgical treatment of spondylolisthesis involves spinal fusion particularly if there is instability or associated pain or dysfunction related to the disc at the level of the spondylolisthesis.

9. Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

The sacroiliac joint connects the bottom of the spine (sacrum) with the iliac area of the pelvis. The sacroiliac joint is the largest joint in the body and serves to distribute forces from the upper body to the lower limbs to allow walking. The sacroiliac joint is normally subjected to large shearing forces as it is the junction of the spine to the legs via the pelvis. In most humans it is a joint that doesn’t move more than a few degrees (2-4 degrees) with the exception of pregnancy where relaxin hormone makes the binding ligaments lax to allow descent of the foetus into the pelvis. Sacroiliac joint dysfunction broadly is either too much or too little movement can arise due to trauma, degenerative changes, pregnancy, spinal fusion or ligamentous laxiety. There are specific inflammatory arthritis disorders such as ankylosing spondylitis which affect the SIJ.

Only 10-20% of patients who present with back pain actually have pain originating from their sacroiliac joint and it is a difficult source of pain to diagnose without injections and scans; clinical history and examination (Laslett’s provocative tests) can be useful in predicting this but insufficient in themselves. Patients with sacroiliac joint dysfunction may experience pain localised to one or both sides of the buttocks. It is typically worse with prolonged sitting, sudden changes of posture and stairs/hills/squats. Pain can often radiate down the back of the leg mimicking the symptoms of sciatica. Other diagnoses such as piriformis syndrome or ischiofemoral impingement should be excluded.

Patients who have undergone spinal fusion surgery have a higher possibility of pain arising from the sacroiliac joint which thought to be due to abnormal mechanical stress transfer on the sacroiliac joint following spinal fusion. It is thought to arise in between 10-30% of patients after spinal fusion involving L5/S1, multiple level fusions or fusions to the pelvis with screws and rods.

Most patients with sacroiliac joint dysfunction can be treated successfully without surgery. Treatment usually involves a short course of anti-inflammatory medication, activity modification, physiotherapy and use of a pelvic brace. Next steps may include injection of glucose or platelet rich plasma (PRP) into the ligaments around the joint to stiffen it up (if hypermobile) or injection of steroid into the articular synovial portion of the joint. Second line treatments include denervation of the joint (radiofrequency denervation and denervation of the surrounding nerves (cluneal nerves).

If non-operative treatment or second line treatments fail, then surgery in the form of fusion either robotically, with navigation or under X-ray control may be recommended for patients who suffer from chronic sacroiliac joint pain. This typically either involves placing cylindrical screws obliquely across the joint or placing pyramidal implants perpendicular to the joint depending on your condition and anatomy. To learn more, the adjacent link is a comprehensive source:

https://www.physio-pedia.com/Sacroiliac_Joint_Force_and_Form_Closure

(L) Cylindrical implants being passed across a sacroiliac joint under computer navigation. (R) Pyramidal implants across left sacroiliac joint

Innervation of the dorsal sacroiliac joint. Slings and relevant musculature for form closure and stability. Concept of form closure (ligaments/joint shape) and force closure (forces of surrounding muscles) when combined produce stability of the sacroiliac joints

10. Coccydynia

Coccydynia (also referred to as coccygodynia or tailbone pain) is pain at the coccyx which is the bone right at the end of the spine situated between the buttock cheeks. Although coccydynia resolves in the majority of patients with supportive care and aids (e.g. seating changes, gel donuts, loose clothes, avoiding constipation), symptoms can persist for months or years and, in some patients, may become a life-long condition. Intractable coccydynia is relatively uncommon, but when it occurs it can dramatically decrease a patient's quality of life.

The coccyx is the lowest region of the vertebral spine, located inferior to the sacrum The coccyx is thought to be a ‘useless’ bone other than its connections to the anal ligament and is thought the be the remnants of evolution from an animal with a tail. The coccyx bears part of the weight when a person is sitting, with an increased weight load on the coccyx when a person leans back, partly reclining, in the sitting position. It is more common in women and younger adults, with pregnancy, trauma, joint hypermobility and inflammatory conditions placing patients at higher risk.

When other treatments have failed and to aid in diagnosis injections of local anaesthetic and steroid either into the painful segment of the coccyx or into the nerve relay station (Ganglion Impar Block) is trialled. If this relieves the pain temporarily but is unsuccessful in longterm relief then removal of the coccyx is considered (coccygectomy). This procedure is usually an overnight stay but can take weeks and months to get over from a sensitivity point of view. The main issue is keeping the wound dry and clean, avoiding excessive pressure and avoiding infection.

11. Osteoporotic fractures and vertebral body fractures

Vertebral body fractures in patients with normal or high bone mass often are caused by high energy mechanisms that disrupt many of the supporting bone and ligament structures rendering them unstable where even relatively normal forces to an injured region in this state can cause poor alignment and nerve compression. These will often need stabilisation either surgically or with bracing.

(Picture on the left) An example of an unstable fracture that required rod/screw fixation 3 levels above and below the injured level.

Vertebroplasty is a minimally invasive procedure performed through keyhole incisions with needles used to treat vertebral compression fractures of the spine by injection of cement into the spinal vertebra to harden the surrounding bone. These painful, wedge-shaped fractures can be caused by osteoporosis and injury. Left untreated, they can lead to a painful and forward bent spine (kyphosis). Many fractures are not suitable for vertebroplasty.

People with bones weakened by osteoporosis (a depletion of calcium) or multiple myeloma (cancer of the bone marrow) are especially prone to compression fractures. Trivial activities in the setting of weakened bone such as lifting a light object, sneezing, or coughing may cause fractures.

Vertebroplasty is a controversial procedure with mixed reviews on its evidence. As a general guide, it is effecting in relieving pain in 75-90% of patients. Sham controlled (‘real’ vertebroplasty procedure compared to fake intervention) randomized control trials have revealed good results provided the intervention is done early (<4-6 weeks) before bone healing. It should only be considered if there is very severe pain limiting movement where the patient is dependent on assistance to get out of bed and heavy medications. Sometimes this procedure is done in conjunction with a biopsy where the cause of fracture is unknown.

For fractures that require intervention but are not suitable for vertebroplasty then spinal stabilisation with instrumentation (e.g. rods and screws) can be required.

In addition to this intervention, the underlying cause of weak bone must be investigated and addressed, where that be for osteoporosis, abnormal growths or cancer, to prevent further fractures. Medical treatments such as bisphosphonates and calcitonin may also give symptomatic relief as well as treating the cause.